Hyper Longevity: How to Make Death Obsolete

Chapter 8 of Super You: How Technology is Revolutionizing What It Means to Be Human

If you came to this chapter expecting to read the magic 10-step certified Super You

process that will help you live a very, very long time, then here it is; although, notice

that it’s only three steps.

- Don’t get sick.

- Avoid accidents.

- Wait.

Easier said than done, right? Don’t get sick? That’s not a step. But you need to invest effort into avoiding it at all costs because unless something bad happens, such as a Whole Foods truck taking you out as you cross the road to buy a Twinkie, then you can pretty much be sure some nasty disease will end your life at some point.

Don’t get sick. We’ll show you what we know about not getting sick in more detail later in this chapter. We’ll then show you how technology (and its accelerating improvement) is going to help you stay healthy. Or cure what ails you.

Step 2 is less controllable. Still, here is the advice, avoid the following: Falling down, guns, cars, poison, suffocation, and water (drowning). Avoid people because they statistically kill the most people, by accident or on purpose. People also kill themselves. It’s hard to avoid yourself. But be vigilant with your mental health.

If you are successful with Steps 1 and 2, and most people are because even though people do die of accidents and disease, the average human lifespan worldwide is 71 (based on 2013 World Health Organization (WHO) data). By the time you read this, it will be pushing toward 75 and in the next decade on its way to 80. Australians live to 83. Canadians live on average longer than Americans. Their lifespan is on average 82.5 years. The Japanese are the longevity champs at 84.6 years.Average American life expectancy in 2014 was a rather sad 79.59.

Step 3 is “wait.” This is deceivingly simple. But we really mean it: Let time go by and stay alive as best you can. Waiting is important because as time goes by, the acceleration of technological improvement will bring new therapies to stave off and eventually mitigate death. We will talk more about this in detail a bit later. When these handy steps help you live a very long time, you can send us a nice thank you card when you turn 100 or 200 … you’ll see.

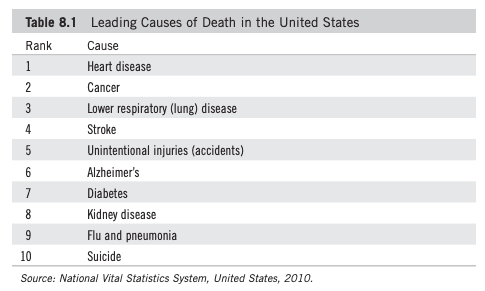

Table 8.1 shows the top ten things that kill people in the United States

A History of Aging

Here’s the best news of all: Life expectancy rates—the median age of death for most people in a given population—has been consistently increasing since early man dropped out of the trees and moved into subdivisions.

Technology helps increase life span so it is no surprise that the trend in technology is similar to the graph of life expectancy rates. Let’s start as close to the beginning as possible. Research efforts to plot the growth

of human life span in early human development have been somewhat daunting.

The passage of time has erased remains of early humans from the prehistoric era. With

access to only the fragments of skeletal remains from archaeological digs, scientists

are limited by the resources at their disposal to conduct their research.

Until recently, this impeded scientists’ ability to uncover the average life expectancy rates of the earliest humans. However, in 2004, anthropology professors Rachel Caspari of Central Michigan University and Sang-Hee Lee of the University of California-Riverside established a revolutionary method of fossil analysis. This allowed them to track the first significant life span shift in the history of mankind.

They use what is called the OY ratio (old to young ratio), which uses bone analysis to measure relative age—instead of the exact age of a person—at the time of death. Using this method, they were able to group bone fragments for the fossilized remains of 768 humans in four regions of the world into categories of “young” and “old.”

When the researchers measured the proportion of young to old in each population, they discovered life span rates increased marginally across most of the time periods except one. Humans living 30,000 years ago had an OY ratio five times greater than earlier populations. For the first time, three generations of the same family coexisted,

and humans lived long enough to become grandparents. Naturally, this discovery is called the “evolution of grandparents.” And the 5 p.m. early bird dinner special was not long behind. (This last bit is speculation, don’t write that in your thesis.)

This sudden increase in life span appears to be related to knowledge transferred from earlier generations. Over time, the oldest people transferred the tools they had for survival to the youngest people. Then the youngest people used existing knowledge to improve upon those tools. Eventually, family members could survive long enough so three generations were living at once.

Caspari and Lee identified the impact of knowledge transference on longevity in another study they published in 2006. They reviewed the OY ratios of Upper Paleolithic Europeans to understand whether life span increases in the population were a result of their biology or their culture. They found that life span increased when modern humans arrived in Europe, bringing new knowledge with them.

The earliest information available that verifies the exact ages of humans at death comes from epitaphs of those who died during the Roman Empire. These show an average lifespan for Romans was 20 to 35 years old. Infectious diseases or infected wounds from accidents or conflicts were the major causes of death. Child mortality

was high as well. However, if Romans survived birth, didn’t contract a deadly disease, or get skewered with a spear, they could live into their 60s and 70s.

Major killers included cholera, tuberculosis, and smallpox. Plagues such as the bubonic plague in the fourteenth century—also known as the Black Death in Europe—wiped out as many as one-third of Europe’s entire population.

Between 1500 and 1800, life expectancy rates rose to between 30 and 40 years. By the 1800s, life expectancy rates had doubled thanks to the Industrial Revolution. Major innovations in manufacturing sparked improved health care, sanitation, access to clean water, and better nutrition. Inventions in transportation, such as the

steam engine, also increased the dissemination of knowledge across continents.

Life expectancy rates have improved gradually in the last couple of hundred years or so between 1800 and 2012. There was a small dip from 1918 to 1919, when the influenza outbreak (disease) and World War I (other people) killed large numbers of the population before age could get them. As we said, it’s illness that greatly shortens most people’s longevity. However, technological innovation in science and medicine is the great tool against illness. For those of you that were around in the 1970s or 1980s, you’ll recall (or if you don’t, ask someone who does) how people related to cancer and AIDS in those decades. These diseases were once pretty much death sentences if you became ill with them. After a diagnosis, you cleaned up your affairs, told the people around you that you love them, and then sooner or later you succumbed to the disease. There was little medical science could do for you, except perhaps help you to suffer less at the end.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there were a series of major health innovations that helped prevent and manage acute and chronic disease. Among them were antibiotics, vaccines, pharmaceuticals, and various medical instruments that advanced treatment capabilities.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, the average global life span was 75. That number is still improving, as has been the long-term trend. As we said earlier, the average American life expectancy in 2014 was 79.59. And guess what’s going to happen to the trend as nanotechnology, stem cell research, robotics, and genetics all continue to progress? Humans will live longer, especially those in developed nations with access to wealth, and of course the

technology to spend that wealth on.

The Methuselah Award Goes to …

If you are going to live a very long disease-free life, then it’s probably helpful to understand who has done the best job at it. And it would be logical to copy that person’s habits, even if that logic is flawed.

Here’s a little story. Once upon a time there lived three very different people who lived on three different continents and led three very different lives. They all were named in the Guinness World Records as record holders for longevity.

• Jeanne Calment—Let’s start with Jeanne Calment, a French woman who lived to 122. Upon her death in 1997, she was referred by the newspaper Le Monde this way: “Elle était un peu notre grand-mère à tous,” which means, “she was a little bit grandmother to us all.” Calment holds the Guinness World Record as the oldest person ever to live. She was born in the south of France and spent her entire life there. She witnessed the building of the Eiffel Tower and met Dutch artist Vincent Van Gogh. Each week, she purportedly ate 2.2 pounds of chocolate paired with a daily glass of port wine. The rest of her diet was rich in olive oil, which she also slathered on her skin in an effort to fight wrinkles.

• Jiroemon Kimura—While Calment ate chocolate and drank port, Jiroemon Kimura, from Japan, was restricting his diet. Kimura is the oldest man that ever lived. He died at age 116. Kimura believed in eating small food portions every couple hours. During his life, he witnessed the reign of four emperors and saw 61 Japanese prime ministers hold office.

• Sarah Knauss—Then there was American Sarah Knauss. She lived three years more than Kimura, dying at the age of 119 in Pennsylvania. The Ford Model T was introduced while she was growing up. She also lived at the time when the Titanic sank in 1912. She was a homemaker and her hobbies included needlepoint and watching golf. Her favorite snacks were milk chocolate truffles, cashews, and potato chips.

So what do all three have in common? They were supercentenarians—people who live to the age of 110 or more.

But besides that, they seemingly have few lifestyle commonalities. For scientists that have studied these long livers, the conclusion is mostly a collective shrug. Nothing about these supercentenarians outwardly suggests any set of strategies that can be copied to produce a longer life in another person.

That said, there has been some significant research in longevity that has produced some interesting results, and this work does suggest actions anyone can take to extend their natural life span.

What We Know About Super Agers

According to the New England Centenarian Study, as of 2014, one person for every

5 million people on the planet will live to 110 or more.

People who live to the age of 100 are called centenarians and their ranks are much more common than they used to be. In 2014, the incidence of centenarians was one for every 5,000 people and that number is steadily growing.

In 1999, data compiled by the United States Census Bureau shows that during the 1990s, the number of American centenarians nearly doubled: 37,000 at the beginning of the decade and 70,000 by the end. Then there are the predictions.

A 2010 edition of TIME magazine reported that by 2050 more than 800,000 Americans will live into their second century of life. Remember, at the start of this chapter, we pointed to a long life strategy called: “Step 3.” It was “wait.” If you can hang on for another 30 years or so, you might be in luck. Compare 800,000 centenarians to data from 2010 when there were only 80,000 centenarians in America. That’s a forecasted tenfold improvement.

In 2013, National Geographic launched a longevity issue with a baby on the cover and a headline that read “This baby will live to be 120.” If that proves to be true, there will be at least 4 million supercentenarians in the United States by 2133.

A more aggressive prediction comes from controversial gerontologist Aubrey de Grey, a world-renowned longevity expert. He is also the chief science officer of the Mountain View, California-based SENS Foundation, a research-focused outreach organization that educates policymakers and the public about how humans can live longer through the “damage-repair” approach to treating age-related disease.

“We are looking at a divide and conquer approach. Dissecting the problem of aging, accumulating (the) damage of old age into sub-problems and addressing those sub-problems individually,” de Grey said. “The problem with aging is that so many things go wrong that we can’t control and fix them all.”

De Grey predicts by 2030 there will be 3 million centenarians worldwide. Based on accelerating technological improvements, he is likely to be right in his forecast, although not everyone agrees with him. A lot of that longevity progress will depend on breakthroughs in heart disease, cancer, and other life-ending diseases. Stem

cell and genetic therapies, organ regeneration, and nanotechnologies will drive the trend.

Longevity Research Is Still Young

Humans only began living to the age of 100 in the twentieth century, so the longevity research field is a relatively youthful one. Most of the work has been done in the last two decades. Aubrey de Grey said, “It’s only been about the last 10 or 15 years that we have been able to start talk about actual theory of concrete plans for delivering medicine that postpones aging.

The majority of the knowledge about longevity today has been obtained by studying super-agers like Calment, Kimura, and Knauss (see “The Methuselah Award Goes to …” earlier in this chapter). The intention is to find out what these people do that the rest of us don’t do that makes them live exceptionally long lives. Researchers study their daily habits to isolate common lifestyle choices. What they have discovered is that gobbling chocolate and slurping port, taking olive oil baths, or eating potato chips while watching golf isn’t the fountain of youth. (But it sounds fun though, doesn’t it?)

What we do know is that what you eat and how you live your life is certainly a major factor. However, your genetics play a big role in how long you live as well. Research from the world’s largest centenarian study, the New England Centenarian Study, shows the ability for an individual to live a long time is 20 percent to 30 percent attributable to their genetic makeup. The remaining 70 percent to 80 percent relates to what you do regularly to stay healthy. One of the core fields of study in longevity science is genetics. If scientists can master genetic engineering and bring everyday genetic therapies to the masses—especially to those that have short genetic fuses and have a family history of short livers—then we are starting to unlock the puzzle on a key factor that can extend longevity.

The Kay Walkers of the world don’t have to worry much on this genetic front because she has two grandmothers that are still alive at 87 and 90. That suggests Kay has good longevity genes.

The Andy Walkers have it a little tougher. His paternal grandfather died young, in his 20s (as a result of war), and his maternal grandfather is unknown. That said, Andy’s father and eldest paternal uncle are mostly healthy in their mid 70s.

In Sean Carruthers’ case, it’s a wild card situation. His father died of a heart attack/stroke at 60, after fighting hypertension most of his life. His mom on the other hand is a hardy 71 and her mom is 95. Sean’s other three grandparents made it to their late 70s or 80s.

Like us, if you want an indicator of your own longevity genetics, look at your grandparents and parents and uncles/aunts and you’ll get a sense of what programming is likely nestled in your genes. One study shows your lifespan can somewhat correlate to your parents’ life span. It has a minimal impact though, and is not a guaranteed indicator of your longevity.

It should be factored in with your lifestyle. Disease in your immediate family might be more of an indicator that your longevity fuse is shorter thanks to your genes. But again, no one factor will predict your lifespan. Twin studies, however, suggest genetics only account for approximately 20 percent to 30 percent of your predictable life span.

You can play against a bad hand dealt to you with two strategies:

• Wait for genetic therapies to adjust for your genetic deficiencies, and

• Adjust your lifestyle to buy time until longevity-extending technologies

arrive.

Lifestyle Secrets: Live Long and Prosper

If genes are 20 percent to 30 percent of the longevity equation, then what accounts for the other 70 percent to 80 percent? Simple. How you live your everyday life.

Your lifestyle significantly affects how long you live. There are some very specific choices you can make that will give you a better shot at a long life than if you are more cavalier about it. It’s supposed to be quite simple: eat nutritious food and engage in regular physical activity. These are the basic health rules most medical professionals advise today (and most of us ignore). To a certain extent these ring true from the research that has been done, though drinking diet “anything” and getting your exercise from video games, doesn’t appear to be the solution to a

hyper-long life. Jane Fonda aerobics and fruit smoothies aren’t either, at least not according to the longevity doctors.

Most of the common sense rules (that are backed up by longevity science) we list here are generally intuitive, although you might find a few surprising:

• Eat less of everything

• Eat nutritiously and consume less animal protein and more beans

• Avoid obesity

• Live with purpose

• Live in a supportive community

• Stay married

• Drink wine in moderation

• Stay active

• Manage your stress

• Don’t smoke or abuse drugs, including alcohol

• Buy lots of books by Kay Walker, Sean Carruthers, and Andy Walker

Although this is by no means a complete and definitive list, it is a general snapshot of what scientists know about lifestyle choices that extend longevity. All except buying our books. That one will just keep you entertained, and it helps us pay for our fleet of yachts.

Longevity scientists have gleaned a lot from their research in the last couple of decades, which extensively includes the study of centenarians. Following is a look at some of the more significant research done on Super Agers.

To download and read the full chapter for free visit: https://bit.ly/31PHbna